Mai Chi – Back to the Body

We Vietnamese have never had a close relationship to our bodies. We are not like Brazilians, who are graceful, sexy, have music in their blood, show, caress and worship their bodies. We are not like Africans, who are strong, enduring, and athletic and express each emotion through a different dance. We are also not like Europeans, who decorate, take care of and listen to their bodies; only Europeans could invent the term wellness – the balance between mind, body and soul.

So what about us? The body, that’s a working tool for farmers and city laborers, and sure, they take care of it, the way they take care of their buffalo or vehicle. It has to function smoothly for a long time, be low on maintenance, easily fixed when broken. Only in the short moments of youth is the body a source of pleasure, but very soon afterwards these pleasures are just the side effects of the reproductive function.

For the elite, it’s even worse.

If there is one thing in common between Confucianism and Christianity, then it’s their hostility towards the body.

One of the first things great men are requested to renounce is sex: the ones who want to serve a lofty goal have to stay away from partnership. And actually, whether for the great or the ordinary, the body is something you need to hide, best covered in layers of textiles. (The most daring thing tradition can show is the hip hugging form of the ao dai dress, and people, mostly patriotic men, still rave endlessly about how this piece of cloth masters the art of praising the body without displaying it). In the learning career of the mandarins there is no place for physical education. Even in văn võ song toàn (being excellent in both literature and martial arts), the perfect manifestation of the all-around talent, the excellence of the body is only measured in its ability to fight. The element of play is still not valued; being athletic is not a virtue. Intellectuals and artists should look skinny, the look of men of words, so weak that they can’t hold a living chicken. At universities, unlike in American colleges, male students excelling in sports are viewed by the girls as only having large extremities, and certainly don’t have the fan base of somebody who has the wording craft or musical talent.

But we are witnessing a shift. Economic boom and modernization brings forth more personal freedom, and something remarkable is happening: Vietnamese aren’t only starting to travel to distant places; they are also going back to themselves and discovering their bodies.

First, they start to show more of it. Every year more and more skin and flesh becomes visible. Society’s moral standards are relaxing. And by now, the Ministry of Culture, once anxiously guarding that the male mane was not longer and the female dress was not shorter than what was prescribed by the Party, seems to have given up. Entertainment stars take the lead, and people follow. On any Saturday night downtown Hanoi, girls on motorbikes doing their procession around Hoan Kiem Lake look like they’ve come directly from the beach of Rio de Janeiro. And that in a country which ten years ago still rivaled North Korea in prudish clothing.

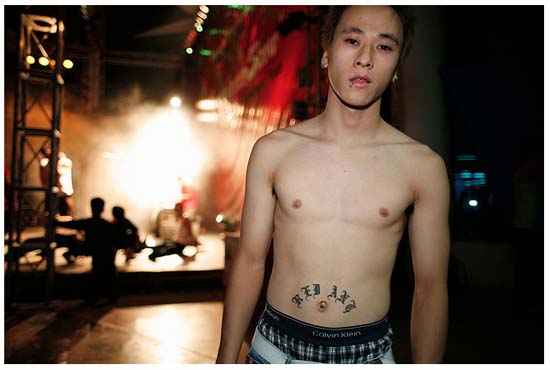

People are also getting busy decorating their bodies. Piercing is still seen as extreme (we are in a country where those running around with pierced noses are mostly cows and buffalos), but tattoos are getting popular. Once the domain of Vietnamese masculinity, especially among those on the edge of society such as home-sick soldiers and petty crooks, women are catching up fast. They love these subtle, easy-to-hide gestures of personal expression. Sometimes you will see a girl, who, judging by her looks, must be a clerk in the Ministry of Agriculture, flaunting a tattooed lower back. Mainstream media have even started to report about “tattoo artists” and, to make the profession look more serious, about their desire “to bring Vietnamese tattoo motifs to the world”. You know: lotus, bamboo and the like. While the chances of inking a Vietnamese ancient bronze drum on the neck of David Beckham might be slim, the ambition might help the sub-culture to be more accepted by the authorities. Currently the tattoo shops are run as beauty salons or without any license at all.

Probably the best evidence of a changing relationship to the body is people’s attitude towards sport. Physical activities are no longer associated with the life of the lower class. On the contrary, while the low ranks now are chained to assembly lines and bound to their motorized tools such as xe ôm, thus having little chance for physical exercise, the ones with means contemplate high-tech bicycles and wage endless online debates about the best water-proof panniers. People start to leave the air-con office to be in the sun and in the rain (but all things need to be done to make sure they can be differentiated from the others, who also are out there in the sun and the rain, but only because they can’t afford to be in an air-con room).

Middle-class lifestyle has evolved: in the 90’s they drank hard liquor and stuffed heavy food into their faces, in the 2000’s they drank wine and started to travel, in this decade, they start to do sport.

In the heightening body awareness, there is a gender bias. The men fall behind – most still just come to the tennis court to have an excuse for more drinking afterwards. Or they move to the golf course, where they sweat less but drink even more. In the meantime, women try everything with their bodies and learn about salsa, belly dancing, pole dancing, aerobics, and yoga. And they flock to the gym.

Nowadays, the new society gathers in gyms, which pop up everywhere with sleek machines, steam baths and giant plasma screens pumping techno music. Working out in the gym is to running in the park what a resort is to a public beach. Going to the gym means that you are modern and dynamic, you can afford the necessary small change, and you are after efficiency. Calories, heart rate, waist size, everything needs to be seriously logged and monitored.

The gyms have an atmosphere similar to the factory halls of the old industrial age. Iron and steel stand in rows; workers, shining in sweat, wrestle with odd-looking apparatus. There is a continuous background noise of clashing iron, buzzing bands, worker’s heavy breath. The only working material here is the body; the only production goal is the shaping of body. Here bodily work is no longer the means; it has become an end in itself. According to Austrian scientist Albert Schirlbauer, gym goers treat their bodies the same way the philosopher Humboldt treats the human mind: both are objects to be improved and beautified through never-ending efforts, which serve themselves alone but not any other purpose.

The gym population is a reflection of the society at large. There are the office workers, squeezing in an aerobic session between work and home chores. More numerous are the business women, obviously with more time on their hands, some of whom consider the gym as an extension of their living room, dropping by in the afternoon with half dozen shopping bags and kids in tow. The bodybuilding freaks discuss their brown, murky muscle juices in plastic bottles and admire themselves in the wall mirror. Then there are the new new-rich, who are as serious about their bodies as about their cars. They get out of their white BMW, disappear into the changing room, emerge in perfectly fitting bikini, baseball cap, IPod glued to arm, and run straight for one hour, getting fit for a world of competition. Only the little oval scar on their right lower leg, the faded mark of a burn from the bike exhaust pipe, reminds of their pre-car past. And similar to the world outside, the lines between classes run deeply. The staffs are mostly skinny, rural boys, their wages lower than the membership fee. After having been around for a while, they have developed an appetite for fitness too. Their main barrier in getting a beautiful physique is that sometimes they cannot afford three meals a day.

The movement back to the body clearly reflects the individualization process happening in society, as people are trying to stand out from the collective, and looking for means to define themselves: my outfit, my tattoo, my body. This process is also made visible by shifting attitudes to life. Unlike the competition and the struggle out there, on the street, where people fight against each other to gain every inch of asphalt, the fight in the gym is a fight against oneself: a little bit faster, a little bit longer, a little bit heavier. The winner is not the strongest or youngest one; it’s the one overcoming himself most.

The movement also offers signals of a number of social changes.

Perception about female beauty has changed: the ideal no longer the ones being weak and fragile. It’s now OK for women to breathe heavily and to be bathed in sweat; even more, they are sexier when doing so.

Maybe in the near future, plump, pale Vietnamese will no longer be the symbol of a life of abundance, but will be associated with low personal discipline and lack of will power, and they will face challenges in the high-end labor market. Fitness, originating from health concerns and discovery of the body, is on the way to becoming a lifestyle in modern Vietnam.

![]()

| Mai Chi is a Hanoi-based arts commentator and contributes to various online media. |

Very good article. We want more of those on Hanoi Grapevine !

Thích bài viết của bạn. Giọng văn rất hay và hóm hỉnh :p

Chỉ có phần về gym thì hơi lan man tí ^^1