Mai Chi – Private Voices

|

|

Thanks to SOI (a Vietnamese website specializing in visual arts) where the original Vietnamese version of this text was posted as a response to the heated debate about the Bui Gallery show, which had been highly anticipated in the art scene. Essentially, one camp of commentators criticized the show as boring and disappointing, claiming that the three Vietnamese artists failed to show personal development, offering no innovation in their new work. The other camp declared their loyalty to the artists and recalled their merits as they were the first to reflect on their inner, individual world at a time when art was still impersonal, mostly depicting propaganda or worn-out themes.

“What we talk about when we talk about love” (title borrowed from a collection of short stories by Raymond Carver – the book was translated into Vietnamese by Dương Tường and Nguyễn Hạnh Quyên in 2009) is not a break-through, not a radical turn as some may have hoped. But the show is special in a different way: using Chinese ink on Dó paper as medium, the exhibition is a humble gesture, offering quiet, private voices, almost whispers. It forces us to slow down, to be attentive if we want to listen. This gesture is rare in the deafening environment of today’s Vietnam.

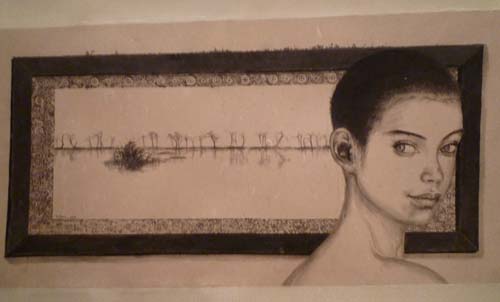

Minh Thanh continues his philosophy as laid out in his last show “Clouds of the old days” in Hue few months ago: humans in and with nature, trying to connect with the “illuminating beauty of the cosmos”, to “touch the whole flawlessness of all things”. Unfortunately, his series on display are not as eloquent as his words; they are rather simple. In “Unsettled Soul”, the portrait is shaggy-haired; nature is bamboo with sharp leaves. The figure in “A beautiful day” and “Blind girl” has a cleanly shaved head, standing in front of still water. The composition of these two pieces is somewhat problematic. In “Blind girl”, nature is depicted in a picture, the frame of the picture inside the picture runs around giving a heavy feel. “Standing alone” is illustrative in a too easy-going way: a bamboo in a naturalistic manner (standing alone).

Quang Huy’s series of women are consistent in their lightness. They are frontal nude torsos, voluptuous, full of life, almost Rubenesque in their image, wearing wide reaching wings made of abstract words. Due to their large size of 1 m x 2 m, their radiance is much more powerful in the real space than on a photograph. Standing below these women (and standing in front of them we really feel like we stand below them), we sense their love, their protection, warm and generous, the kind of feeling we get when being near our mothers and sisters. The works convince with the economy of lines and colors, perhaps with the exception of a waste, an unnecessary detail: the full lips taking the place of the figure’s heads.

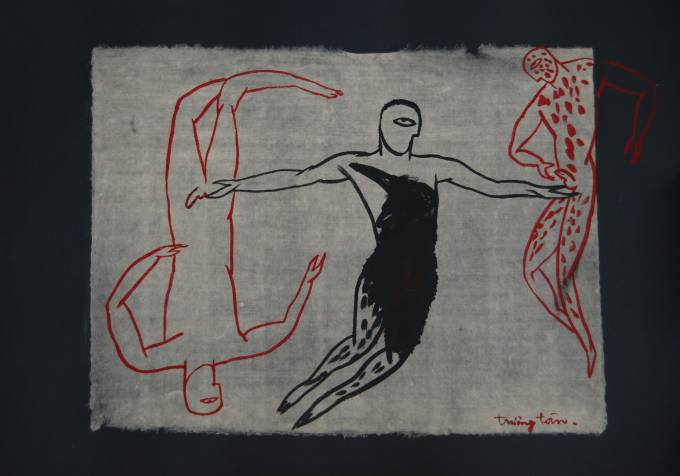

It’s interesting to view Truong Tan’s old works in a contemporary setting. After fifteen years, they have lost their shocking impact, even to the mainstream. On the contrary, they are now beautiful in an almost classical way, with men in profile like on Greek pottery, robust composition and lines drawn with utmost accuracy. Today these graffiti’s are even closer to the real world: lonely people, broken words, incapability of communication, raw energies and longing to be loved.

In Vietnam of 2011, raw, cross, and full of brutal luxury, Minh Thanh’s call for spiritual love and Quang Huy’s belief in the redemptive power of love seem almost lost voices. And Truong Tan’s figures go on in the agony of their silent desperation. This they have in common with the people of Raymond Carver’s world.

Note: Reprinted with permission from SOI

KVT also has a review about this exhibition, click here to read.

![]()

| Mai Chi is a Hanoi-based arts commentator and has been contributing to various online media. |