KVT – Three Songs of Bopha Xorigia Le Huy Hoang

(Vietnamese version available / Hiện đã có bản tiếng Việt)

SONGLINES

I have seen three songlines created by artist Le Huy Hoang. Each of these sang the song of where he’d come from, where he was.

Now that two months have passed since his death of cancer, just before Tet, 2014, I want to honor these landmarks that trace a route through his personal landscape.

Song One:

SONG OF THE SCARF

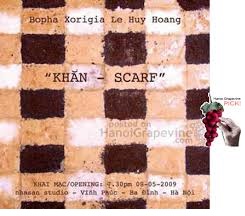

On his 43rd birthday, 09/05/2009, Bopha Xorigia Le Huy Hoang unveiled an installation in the undercroft gallery at Nha San Studio in Hanoi

It was an immediate hit. I called it sublime.

The Scarf, a huge floor installation figuratively representing a checked scarf, or Khan, commonly worn by Cambodian and Khmer rural people (and a favorite tourist souvenir), was awesome…. constructed of squares of Vietnamese coffee grounds and squares of Cambodian and Vietnamese sugar on a white ground.

The fringes at each end in coffee grounds of different shades, and threads of white sugar. Pristine, as the artist intended it to be, it was outstanding, but with the early summer rainstorms causing teeny rivulets to lace the stilt house floor, a sublime sublimation took place and with the dissolving of the mediums in parts of the installation it took on the look of a well worn, well loved piece of apparel as described by the artist below in an interview with the exhibition’s curator, Hung Nguyen Manh

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D7Cu1SOsN6Y[/youtube]

I was intrigued and asked the artist for an Interview which was officially edited and published in a Vietnamese magazine. The tale that unfolded and which I paraphrase below, could be the basis of a great novel, a play or movie.

…… spread in the undercroft was a huge brown and white checked Khmer scarf so beautiful that it looked real.

It measured three by ten meters. As I slowly edged closer I realized that it had been constructed with sugar and coffee and, as the weather was unseasonably wet, the humidity was slowly melding the mediums and the once pristine scarf was taking on the appearance of a well worn piece of apparel in which the dyes had long ago run into each other.

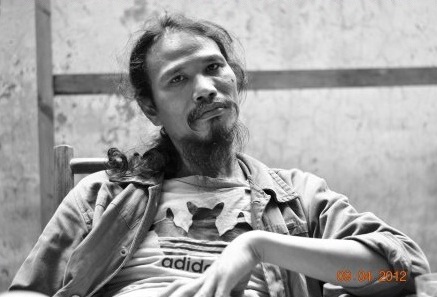

Bopha Xorigia Le Huy Hoang, or Hoang as I‘ll refer to him from now on, is a handsome 43 year old man who looks every thin centimeter the wispy bearded bohemian artist of everyone’s imagination. He could be the poster promo for a Vietnamese version of the opera La Boheme.

He’s a passionate man, has a wife and young daughter and lives and works in a semi rural area not too far from confluence of the Red and Duong Rivers on the outskirts of Hanoi.

His father was a Khmer who joined with the Viet Minh to fight a guerilla war against the colonial French presence in Indo China. When the French were forced from the region the newly elected leader of Cambodia, Noradom Sihanouk, became openly hostile to his former communist allies and in the late 1950’s most had to flee into the unfriendly jungles of bordering South Vietnam. Many made it, under the leadership of Son Ngoc Minh, to the welcoming sanctuary Ho Chi Minh’s North Vietnam and Hanoi. The adolescent foot soldier was one of these and at the conclusion of his secondary education in Hanoi he was given a place in the Medical University and after became a doctor at a Hospital in Ha Dong

During the American war with bombers indiscriminately targeting civilian areas in Hanoi the hospital staff and patients were evacuated to Van Vo village in Ha Tay province. In the neighboring village of Chung a school had been established to educate children of families who had fled the repressive regime of President Diem in the south. The young doctor fell in love with one of the teachers and they married in 1965.

Hoang was born in 1967 and with the escalation of bombing attacks the family was forced to move to a variety of safe locations.

In 1969 President Nixon approved carpet bombing raids on Cambodian border areas to wipe out North Vietnamese supply bases along the southern reaches of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. As the intense saturation bombing attacks continued further into the country, Khmer peasant farmers began to sympathize with the Khmer communist forces, the Khmer Rouge, a name derisively given to them by a dismissive Sihanouk.

In 1970, just after a second son had been born, Hoang’s father was instructed to head back to Kampuchea to join the revolution led by Pol Pot.

That was the last the family heard of him.

Hoang spent his childhood in the riverside, provincial town of Son Tay, about fifty kilometers west of Hanoi. At 13 he was chosen to attend the free army school in Hung Yen, about the same distance east of the capital. When 17 he was selected to join an army mobile training unit in Saigon where he studied and worked until he was 20.

By now the Vietnamese forces were preparing to leave Cambodia having defensively invaded it in 1975 in retaliation for bloody Khmer Rouge attacks in the Mekong Delta provinces that had slaughtered thousands of Vietnamese civilians. They had deposed the Pol Pot regime in Phnom Penh, established a provisional government and, while still skirmishing with remnants along the Thai border, oversaw a reconstruction of the liberated country.

It was to Phnom Penh in 1989, the year that Vietnamese forces withdrew from the country, that Hoang was sent to study the Khmer language (more information from Hoang in the earlier You Tube Link). Many Cambodians thought he was a spy and treated him with contempt and distrust. It was a stage in his life when he was attempting to resolve the dual parts of his being and as pressure built on all sides he took it into his head to go to leave both behind. With other, mainly economic, refugees he went by boat to southern Thailand and spent the next five years in limbo, interned in a holding camp.

There he worked as a jack of all trades and met his first artistic mentor, an elderly man who was earning small amounts of money painting portraits. He took Hoang under his wing and in return for alcohol which Hoang smuggled into the camp at night after scaling the fence, gave the young man a competent training in drawing and painting.

When Vietnamese government officials came to the camp and tried to persuade Vietnamese refugees to return to Vietnam, Hoang, realizing the futility of his position, acquiesced and after questioning by officials in Ho Chi Minh City was reunited with his mother who’d come south to welcome him home.

Because he had no professional training and because he was unsettled he worked as an itinerant laborer traveling around the country until one day he fell in with Bang Si Nguyen, a seventy year old poet and artist who recognized the young man’s passionate, creative personality and advised him to become a real artist.

As a twenty nine year old he applied for a place at the Hanoi University of Fine Art, was accepted after three attempts at the Entrance Exam. He graduated in 2003 and began his ascent into the art world of Hanoi and beyond

For his final examination thesis and folio Hoang returned to Cambodia intent on examining the architecture of Angkor Watt but as he realized more and more the dichotomy of his ancestry he became determined to come to terms with his Khmer roots and since then his art has been primarily concerned with this.

As he got older Hoang says “his heart got bigger” and every time he returns to Cambodia he feels more and more part of the country and has a burning desire to work with the poor there. Until this is possible he continues to play with the emotions and obsessions that bind him to two countries.

He is intent on working with the concepts of displacement and dispossession of the poor and when he was a participant at an art festival in Phnom Pen in 2008 the idea of the Khmer scarf came to him. An idea to help resolve his inner struggles of identity and to forge an understanding of two neighboring cultures

The scarf is symbolic of the Khmer rural poor. It has long been the object they carry that identifies them. At first Hoang wanted to make his scarf of processed cane sugar from the north of Vietnam and Cambodian palm sugar, sugar to represent the culture of the two nations that run, as he says, so sweetly inside him

As the concept developed he realized that he needed another medium to give contrast and he hit upon coffee, a crop and drink that is synonymous with both cultures. He collected used coffee grounds from coffee shops near his home to represent the darkness and bitterness that sometimes envelopes him as he deals with the legacy left by the abandonment and disappearance of his father and the unease that creeps upon him about the death of his father or of his collaboration with the Pol Pot regime.

The scarf was an ephemeral piece and after dissolving, drying, solidifying and then blowing about in summer breezes became a memory.

Hoang had hoped that one day he’d be able to reconstruct the scarf in his originally intended 3 x 20 meter dimensions. I always imagined it singing its powerful song in a major biennale or in the permanent collection of an important museum of contemporary art

Better than that was his vision of the scarf unfurled in dried blood and crushed bone. Preferably on a killing field in Cambodia. Anywhere it would be a stunning statement and a truly marvelous piece of art

SONG OF THE SCARF: KVT/ 2014

Many thanks to Jamie Maxtone –Graham for assistance in providing some images during my research

Read more of KVT’s tributes to artist Le Huy Hoang:

KVT – Three Songs of Bopha Xorigia Le Huy Hoang – Part 2: Rain

KVT – Three Songs of Bopha Xorigia Le Huy Hoang – Part 3: Wall

| Kiem Van Tim is a keen observer of life in general and the Hanoi cultural scene in particular and offers some of these observations to the Grapevine. KVT insists that these observations and opinion pieces are not critical reviews. Please see our Comment Guidelines / Moderation Policy and add your thoughts in the comment field below. |