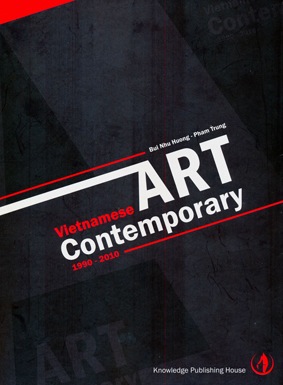

Ilza Burchett – Vài nhận xét về cuốn ‘Nghệ thuật Đương đại Việt Nam 1990-2010″

Ilza nhận xét về cuốn “Nghệ thuật đương đại Việt Nam 1990-2010” của hai tác giả Phạm Trung & Bùi Như Hương, do Nhà xuất bản Tri Thức xuất bản năm 2012.

Khái quát:

Bìa mềm thiết kế bắt mắt, 224 trang bóng, kèm ảnh chất lượng cao minh họa các tác phẩm nghệ thuật và chân dung nghệ sỹ (không được đánh số).

Bố cục trình bày nhìn chung là tốt.

Ngôn ngữ tiếng Anh được sử dụng tương đối ổn thỏa, có thể coi đây là một bản dịch tốt.

Có một số lỗi bản in đáng chú ý về từ ngữ và các ký hiệu, đánh số tên tiêu đề không thống nhất với số trang trong mục lục và một số tiêu đề bị thay đổi từ ngữ trong phần nội dung và phần mục lục.

Mục lục được đưa vào cuối sách ở trang 223 thay vì những trang đầu tiên (giống như trong các tài liệu học thuật), điều này không thông dụng lắm trong giới xuất bản sách, do đó làm cuốn sách trở nên khó theo dõi đối với người đọc.

Có liệt kê tài liệu tham khảo và liên hệ tiểu sử.

Số lượng xuất bản: 1000 cuốn.

Kết cấu: Nội dung được chia thành ba phần như có nói đến trong phần Giới thiệu và Mục lục.

Nhận xét về nội dung:

Cuốn sách đã cố gắng dẫn chứng cũng như ghi chép lại sự phát triển và tiến hóa của thực tiễn bối cảnh nghệ thuật thị giác đương đại tại Việt Nam trong hai thập kỷ 1990-2010. Các tác giả đã chỉ rõ rằng cuốn sách không nhằm mục đích đưa ra những nghiên cứu ghi chép đầy đủ, hay khảo sát chi tiết toàn bộ bối cảnh nghệ thuật đương đại tại Việt Nam trong những thập kỷ qua. Mà họ chỉ tập trung vào nghiên cứu các hoạt động nghệ thuật đương đại tại Việt Nam theo những loại hình đã được thiết lập vững chắc trong giới nghệ thuật thị giác đương đại, cụ thể là: nghệ thuật sắp đặt, trình diễn và nghệ thuật video, những loại hình đã tìm thấy lối đi cho mình trong cách biểu đạt nghệ thuật của các nghệ sĩ Việt Nam trong hai thập kỷ vừa qua, kết quả của giai đoạn Đổi Mới và toàn cầu hóa, song hành cùng các loại hình nghệ thuật lâu đời như hội họa và tranh in vốn cũng đang dần hiện đại hoá nội dung và vai trò của mình trong quá trình này.

Phần I (Định nghĩa Nghệ thuật Đương đại) mở ra với hai câu hỏi: “Nghệ thuật đương đại là gì, và có chất lượng đương đại có nghĩa là gì?” buộc các tác giả phải tự mình đưa ra cho độc giả định nghĩa của thuật ngữ “nghệ thuật đương đại” đồng thời phải lập luận bảo vệ quan điểm về định nghĩa đó. Tuy nhiên, theo ý kiến của nhà phê bình này thì họ đã đơn giản là nhầm lẫn giữa mô tả và định nghĩa. Định nghĩa của thuật ngữ “nghệ thuật đương đại” cần được đứng độc lập không có sự can thiệp, và nếu có can thiệp thì cũng phải dựa trên ý nghĩa tự mô tả thực tế của nó.

Cuốn sách đã chạm đến những vấn đề tranh cãi về mặt xã hội cũng như văn hóa xung quanh việc chấp nhận các loại hình nghệ thuật đương đại có phần mới mẻ ở Việt Nam thời bấy giờ như nghệ thuật trình diễn, nghệ thuật sắp đặt, v.v, được thực hiện bởi các nghệ sĩ Việt, đồng thời giải thích rằng “… đó cũng là một cú sốc cho các giác quan bởi sự thách thức lý tưởng thẩm mỹ truyền thống và can thiệp trực tiếp vào các vấn đề chính trị, xã hội, môi trường và con người trong thời đại toàn cầu hóa.”

If only every book review were this incisively written! It is scholarly, but also helpful in a practical sense. It is descriptive, but also analytic. What were the book’s authors trying to do? Did they succeed? Does it matter?

This his review is helpful to the purchaser/consumer at two levels. First, to help me decide if I want to go out and buy it. Second, to help me get the most out of the book once I own it.

It is also helpful to the authors, for their next effort, if they are open to constructive criticism. The best example is the Table of Contents being placed in the back of the book, rather than the front (where European readers expect it). This is common in VN books. It would seem a wise move to include two Tables of Contents, one at the front and one at the back, to make the book user-friendly for both domestic (VN) and foreign readers. Why go to all the trouble of translating the book into English language and then fail to format it in a way that helps people who are accustomed to the non-VN way of setting up books?

So, a review helpful to just about everyone. Who could ask for more?

Many thanks Mark — truly appreciate your assessment and feedback.

Ilsa’s review of a Vietnamese sculptor’s works, also on Hanoi Grapevine not long ago, revealed the mind and sensibility of a sharp art critic. This book review confirms them. Many thanks to you, Ilsa, and to Grapevine, for such a reading pleasure.

For me, the location of that Table of Contents is not a problem. Our habits should not be taken for granted as “should be” things. While in Hanoi, just see things the Hanoi ways. We should not complain that the grapevine here is so different from the grapevine in the Napa Valley or other places in this world. Change our habits, and we’ll be able to enjoy, even ourselves.

Why in English and not Vietnamese first? Perhaps that’s one way to get the book out safely first – the Vietnamese version might get stuck in the censorship here, or born as a child badly maimed by the Agent Orange.

One last note: the English of this book is the best of all the art books published so far by and in Viet Nam. Congratulations and many thanks to the translators.

Many thanks Trinh Lu.

Your advice is taken — one never stops learning…

Comment on Ilza Burchett’s review of “Vietnamese Contemporary Art”

Nguyen Dinh Dang

In the first section of the recent review of the monograph “Vietnamese Contemporary Art” by Bui Nhu Huong and Pham Trung, Ilza Burchett blamed the authors that they confused definition with description of contemporary art but she failed herself to give a proper definition of contemporary art as well. As a matter of fact, the paragraph she cites from Kathrin Busch is not a definition of contemporary art, but only points out some aspects (not the essence) of contemporary art such as its high saturation of theoretical knowledge, that contemporary art becomes a research or an independent form of knowledge itself, etc. But these aspects are so generic as they can be applied to Renaissance, Baroque, Classical, Impressionism arts, etc, as well. We all know that the theory of linear perspective was worked out in the treatise by Piero Della Francesca, that the paintings and drawings by Leonardo da Vinci are based on his pioneering and outstanding knowledge of human anatomy. In this sense, the “definition” by Kathrin Busch has the same quality as that by the authors of “Vietnamese Contemporary Art”. These authors have already pointed out the difficulties, which on faces when attempting to give a “definition” to contemporary art. In fact, a definition as such does not exist. What we have is just a diversity of notions.

Next, by stating that “Contemporary artists that claim or happened to have no interest, access or exposure, or do not wish to engage in any way with philosophical thought for whatever reasons, are nevertheless subject to our ‘contemporary’ world, which is infused with information of all sorts, unavoidably impacting on their work,” Ilza Burchett contradicts herself. Her statement effectively means that contemporary artists may actually not need any theoretical background or philosophical thought at all, but are nonetheless “contemporary” simply because they live and create in our time.

Contemporary art is not the postmodernism as a philosophical concept. The fact that one may have to study the mimesis theory of art by Plato and Aristotle and/or postmodern theory in art colleges does not mean that mimesis and/or postmodern theory define contemporary art[1]. According to J.F. Lyotard, “the text he (i.e. the postmodern artist) writes, the work he produces are not in principle governed by preestablished rules, and they cannot be judged according to a determining judgment, by applying familiar categories to the text or to the work. Those rules and categories are what the work of art itself are looking for. The artist and the writer, then, are working without rules in order to formulate the rules of what will have been done.”[2] In other words, postmodern art is like traffic in Hanoi, where the only rule is no rule.

Moreover, contemporary art, understood as art of our present time, is no longer postmodern either. The postmodern time has effectively been finished at the end of the Cold War (around 1990). The invention of the internet and world-wide web in 1992 – 1994, the digital age, and the new situations in the world including the collapse of the communist bloc, the fall of dictatorship and totalitarian regimes, the worldwide blossom of democracy, the war on terrorism, the rise of nationalist expansionism in East Asia, global warming, the recession of the nuclear power plants after the Fukushima disaster, etc. are just some developments, which actually turned a new page in human history. The present condition in the world forces us to deeply question our attitude we bear since the postmodern time, where truth and justice were replaced with group consesus, good performance, commodity, and profits. Artists are not exempted from this common tendency because, before being an artist, one is a human being, a citizen notwithstanding a citizen of the world, or a cosmopolitan. Once again, we see that the artistic values that the artist puts into the creation of an art work are becoming important apart from its commercial value. The reverence for the artist’s skill is growing. We see more and more appreciation for the painters, who can actually draw and paint, the sculptors who can actually sculpt, the novelists who can actually write.

10/1/2013

[1] One should be very careful in selective reading to avoid falling into the pseudoscientific nonsense written the works by the postmodern “intellectuals-geniuses” like Jean Baudrillard, Gilles Deleuze or Felix Guatarri.

[2] J.F. Lyotard, The postmodern condition: A report on knowledge (Manchester University Press, 1984).

I found at least 2 typos in my previous comment. I would like to ask you to kindly correct them, namely:

1) In the last paragraph:

group consesus -> group consensus

2) In the footnote [1]:

nonsense written the works… -> nonsense written in the works…

Thank you.

Dear Nguyễn Đình Đăng,

… I am sorry, but I do suggest you re-read my text more carefully as there is no point for me repeating what I have already said — in defense of the said…